Shostakovich String Quartet No. 8

1)

What was Dmitri Shostakovich trying to portray in his music? There is probably no more debated question in 20th-century Western classical music than this. On the surface, it seems to have a simple answer.

2)

Shostakovich expressed his thoughts and feelings in his music, as any composer would. And this is undoubtedly true. Above all, Shostakovich was one of the great composers in history.

His mastery of form, melody, structure, tempo, and ability to find an almost universal expression of grief and passion is virtually unparalleled among composers. That much is apparent to those of us who love Shostakovich's music.

3)

But everything else, including the thorny question of what his music MEANS, is much, much, much less clear. Practically all of Shostakovich's life was lived in the shadow of Soviet Russia, and of course, his musical career was in that shadow.

This means there is always a sometimes impenetrable layer of secrecy, mystery and doubt beneath the surface of Shostakovich's music.

4)

In 1960, Kruschev, who had loudly trumpeted Shostakovich's name to the Western press as an example of a free Soviet artist after the excesses of the Stalin regime, decided that Shostakovich should be the new head of the Russian Union of Composers.

5)

The catch was that Shostakovich would have to join the Communist Party to take the job. Shostakovich, who had long resisted becoming a full party member, Party.

Shostakovich was disappointed with himself, as his friend Lev Lebedinsky wrote: I'll never forget some of the things he said that night [before he joined the Party], Partying hysterically: I'm scared to death of them.

6)

Why does all this matter? Because just a few days after joining the Communist Party, and after meeting his friends Isaac Glikman and Lev Lebedinsky, Shostakovich travelled to East Germany - Dresden, to be precise - to work on a film commemorating the destruction of the city during the Second World War.

7)

He was supposed to write music for this film, but instead, Shostakovich sat down and wrote his 8th String Quartet in THREE DAYS.

He later wrote to Glikman: "No matter how hard I tried to fulfil my obligations to the film, I just couldn't. Instead, I wrote an ideologically flawed quartet that nobody needs.

8)

I thought that if I died, it was unlikely that anyone would write a quartet in my memory. So I decided to write it myself. You could even register on the cover: Dedicated to the memory of the composer of this quartet.

Today on the show, we will explore this remarkable piece together - join us!

Shostakovich String Quartet No. 8

https://stickynotespodcast.libsyn.com/shostakovich-string-quartet-no-8

Schostakovich Quartet No. 8 - Jansen, McElravy, Rachlin, Maisky

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wokx576v5Y0

Shostakovich - String Quartet No. 8 in C minor Op. 110

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tby5aMrMu6Q

[About Shostakovich's String Quartet No. 8 (1960) Part 2] [February 14, 2016 (Sun)]

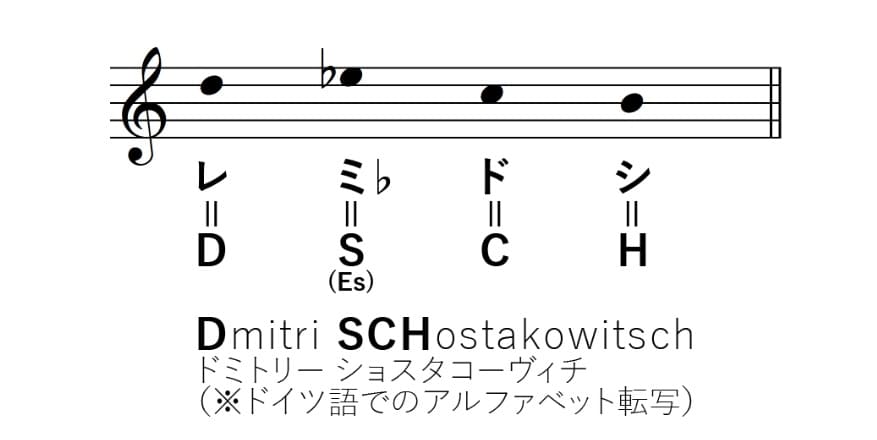

Composer Shostakovich dedicated String Quartet No. 8 to his own memory. But what does "dedicate to one's own memory" mean? The key to unlocking this secret is hidden in the "sound pattern made up of four notes" played by the cello at the beginning of the piece (see the image of the musical score).

https://blog.canpan.info/music-dialogue/archive/63

Shostakovich String Quartet No. 8

https://www.tokyo-harusai.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2022_yayoi_toda.pdf

This work was written in just three days during a visit to Dresden in 1960, where the scars of World War II bombing still lingered. The Beethoven String Quartet first performed it in Leningrad on October 2 that year. Dedicated to "the memory of the victims of fascism and war", it uses Shostakovich's signature "DSCH" sound, making it clear that the work is deeply personal to him. He has quoted from many of his works, including Symphonies Nos. 1, 5 and 10, Cello Concerto No. 1, Piano Trio No. 2 and the opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk County. In his works are quotations from Dies Ire, Russian funeral songs, Siegfried's Funeral March, and Tchaikovsky's Pathétique. All five movements, all in a minor key, are played without interruption. The first, fourth and fifth movements are largo, and the second and third are allegro. The mocking dance of the Grim Reaper, the piercing pain and the never-ending lamentations are sharply and cynically depicted.

Shostakovich: String Quartet No.8 - The Sound of Despair (Understanding Music)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a9W5LdYCkj0

Add info)

The Degenerates: Music Suppressed By The Nazis

https://stickynotespodcast.libsyn.com/the-degenerates-music-suppressed-by-the-nazis

The centre of Western Classical Music, ever since the time of Bach, has been modern-day Germany and Austria. You can trace a line from Bach and Haydn to Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, and Wagner, and finally to Mahler. But why does that line stop in 1911, Mahler's death?

Part of the answer is the increasing influence of composers outside the Austro-German canon, which has enriched Western Classical music. There was also World War I getting in the way. But after the war, one could have expected that this line would continue again. The 1920s in Germany and the rest of Europe were a time of radical experimentation, a flowering of ideas, and a wild ecstasy of innovation across all the arts. So why don't we hear of these Austro-German experimenters and innovators anymore?

Because of Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels, and their Entartete, or Degenerate music, Hitler's worst crime was by no means his suppression of dozens of German, Austrian, and Eastern European composers. Still, it is a fact that from the end of World War I until 1933, classical music in Germany and Eastern Europe(especially Czechoslovakia) was flourishing, with composers such as Zemlinsky, Krenek, Korngold, Schreker, Schulhoff, Haas, Krasa, and Ullmann taking up the mantle of the giants of the past and hoisting it upon themselves to carry it forward.

The Nazis silenced, exiled, or killed off many of these musicians during the twelve years of 1933-1945, and those voices are forever lost, but the music they wrote before, during the War and the Holocaust, and after it, some of its masterpieces entirely on the level of their predecessors, has been preserved.

So why, then, are these composers not better known? I've chosen 12 composers, all writing music at the highest level. Some may be familiar to you, but many probably won't. Through all of their trials and tribulations, one of the things I want to emphasize throughout these stories, even the bleakest ones, is that so many of them found the will to be able to compose this heart-rending, beautiful, and often optimistic music, all as they witnessed unimaginable horrors.

It may seem empty when the end for many of these artists was so horrific, but these compositions and the men and women behind them are a true testament to the resilience of the human spirit. These artists created a life for their friends, neighbours, and inmates in concentration camps. They wrote music they knew would almost certainly not be heard in their lifetimes, from an urge that could not be destroyed, even by gas chambers. Join us to learn about them this week.